|

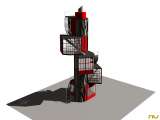

modelo interpretativo

|

|

|

|

|

redibujado

|

|

Edificio para el Leningradskja Pravda, planos |

análisis

|

En 1924 se convocĂł un concurso para la construcciĂłn de una torre para el Leningrádskaya Pravda (La verdad de Leningrado–la actual San Petersburgo) en la capital de la UniĂłn SoviĂ©tica. El espacio disponible era mĂnimo: un cuadrado de 6 x 6 metros en la plaza Strásnaya (Strastnoy) –hoy Plaza Pushkin—ubicada sobre la traza del Boulevard Strastnoy, que limitaba el segundo y tercer anillo de MoscĂş, y junto a una de las calles radiales que conectaban con el Kremlin. La privilegiada ubicaciĂłn de la torre es similar a la elegida por El Lissitsky para sus rascacielos horizontales y estructuras conmemorativas y revela la intenciĂłn propagandĂstica de esa ocupaciĂłn de las principales plazas de la ciudad con manifestaciones del arte revolucionario. Por lo tanto, no sorprende el listado de arquitectos que se presentan al concurso: los hermanos Vesnin, Golosov, Guinsburg y el propio Melnikov, todos ellos miembros destacados de las filas constructivistas. Usando palabras del crĂtico formalista VĂctor Sklovsky, habrá que ver, entonces, “la disimilitud de lo similar” para destacar los valores de este proyecto entre esos otros, todos ellos dispuestos a expresar los sĂmbolos revolucionarios, el ritmo nuevo de la ciudad, el clamor modernizador. El proyecto de Melnikov partĂa de un nĂşcleo cilĂndrico de hormigĂłn que alojaba una caja de escaleras de caracol y un ascensor. En torno a ese nĂşcleo rotaban cuatro mĂłdulos de acero y vidrio, suspendidos en voladizo mediante unas guĂas y perfiles metálicos, una idea que repetirá en los croquis realizados para el concurso del PabellĂłn de ParĂs de 1925. Su propuesta parecĂa mezclar ideas presentes tambiĂ©n en la propuesta de los hermanos Vesnin—ganadores del concurso—y de Golosov, como la incorporaciĂłn del movimiento –el tiempo—como un material nuevo para la arquitectura, los efectos de la transparencia o el hormigĂłn armado. Pero mientras los Vesnin promovĂan la visiĂłn del movimiento vertical del ascensor o la del cartel en la coronaciĂłn de la torre, Melnikov parecĂa más interesado en buscar la mayor variedad de posiciones de esos mĂłdulos mĂłviles y , consecuentemente, la infinita riqueza de efectos y de luz en todo el edificio. Y si bien utilizaba una estructura de hormigĂłn como Golosov, mientras que este modelaba el material forzándole a adoptar complicadas formas estrelladas o cilĂndricas, Melnikov lo interpretaba como un nĂşcleo encastado en el terreno para compensar el esfuerzo al que la estructura serĂa sometida por la rotaciĂłn de los forjados. A partir de aquĂ, la comprensiĂłn tĂ©cnica del funcionamiento del edificio se hace compleja. Los materiales dejados por Melnikov sĂłlo permiten especular sobre la forma y el funcionamiento de sus elementos básicos: los soportes inferiores en voladizo y la forma de cada mĂłdulo. El modelo y dibujos que aquĂ se muestran se basa en una lectura atenta del proyecto y de sus interpretaciones más destacadas (la de O. Mácel-R. Nottrot y la de E.Steiner). Podemos comprobar en ellos aspectos complementarios como la forma trapezoidal del mĂłdulo(con un lado recto y uno curvo), y las articulaciones entre las terrazas y escaleras exteriores. (F.A.P.) |

obras relacionadas

|

Casa Melnikov

Club Rusakov Faro de ColĂłn PabellĂłn de la URSS |

bibliografĂa

|

Redibujado y modelo interpretativo realizado por: 2005 - Javier Bas, Victor Gonzales Joan Sureda |

|

VV.AA.(con textos de Otokar Mácel, Ton SalvadĂł, GinĂ©s Garrido, MoisĂ©s Puente, Federico Soriano et altri) Konstantin S. Melnikov. Madrid: Electa, 2001. VV.AA. Vanguardia SoviĂ©tica 1918-1933: Arquitectura realizada. Barcelona: Lunwerg Editors, 1996. COOKE, Catherine; KAZUS, Igor. Soviet architectural competitions 1924-1936. Londres: Phaidon, 1992. KHAN-MAGOMEDOV, Selim O. Pioneers of Soviet architecture. Londres: Thames and Hudson, 1989. KonstantĂn S. Melnikov. Madrid: Ed. Electa, Instituto de Juan Herrera, Escuela TĂ©cnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid, 2004. SALVADĂ“, Ton (ed.), COHEN, J. L. COOKE, C. STRIGALER, A.A. TAFURI, M. Constructivismo Ruso. Barcelona: Ed. Del Serbal, 1994. |

comentarios/ensayos